- Researchers grew plants in soil from the moon for the first time.

- Though the seedlings experienced stress and stunted growth, they still sprouted.

- Cultivating crops on the moon may help future space travelers survive longer missions, researchers said.

For the first time, scientists have grown plants in soil from the moon. Their insights could one day help future space farmers grow earthly plants on other worlds.

In a new study, published Thursday in the journal Communications Biology, researchers at the University of Florida planted seeds in samples of soil from the moon, more properly called lunar regolith, which was brought to Earth a half-century ago by the Apollo astronauts.

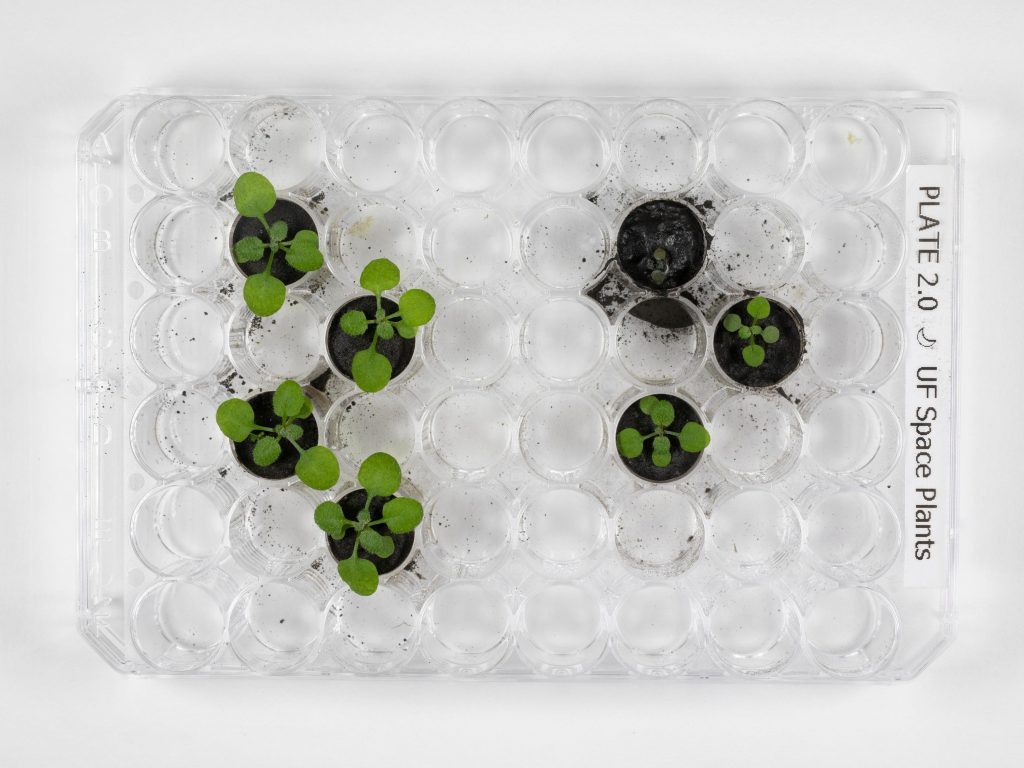

The experiment consisted of using 12 grams — just a few teaspoons — of lunar soil collected during the Apollo 11, 12, and 17 missions, along with a control group of volcanic soil from Earth, which has a similar composition to lunar dirt. Researchers planted seeds of fast-growing thale cress, a weedy plant, which is often used in science due to its fully mapped genetic code. The seeds sprouted within three days.

"We were filled with wonder as we handled these samples, collected by Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, Pete Conrad, Alan Bean, Gene Cernan, Harrison Schmidt, and the other moonwalkers of the 1960s and 1970s," the research team wrote in an opinion piece for The Hill. "Seeing the seeds sprout was awe-inspiring, knowing that our research may one day help astronauts grow plants as a source of food and oxygen during deep space missions and long stays on the moon."

Houston, we have a plant

Reliably cultivating crops in space will be necessary for would-be space travelers to survive longer missions, according to Rob Ferl, one of the study authors and a professor of horticultural sciences at the University of Florida.

"For future, longer space missions, we may use the moon as a hub or launching pad. It makes sense that we would want to use the soil that's already there to grow plants," Ferl said in a statement. "So, what happens when you grow plants in lunar soil, something that is totally outside of a plant's evolutionary experience? What would plants do in a lunar greenhouse? Could we have lunar farmers?"

Perhaps unsurprisingly, researchers found that the plants grew better in the earthly volcanic ash than they did lunar soil. But they could grow.

"We found that plants do indeed grow in lunar regolith. However, they respond as if they're growing in a stressful situation," Anna-Lisa Paul, a research professor of horticultural sciences at University of Florida and co-author of the study, told reporters at a press conference ahead of the announcement.

The plants grown in lunar dirt were smaller and grew more slowly than their counterparts grown in soil from Earth. Many of their leaves had black-and-red discoloration, indicative of stress and overall ill-health. A genetic analysis of the plants revealed those grown in lunar soil expressed genes related to salt and oxidative stress.

Lunar soil is vastly different from the soil that plants typically grow in on Earth: "The moon is very, very poor in water, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus. So naturally lunar soils don't have a lot of nutrients that are needed to support plant growth," Stephen Elardo, assistant professor of geology at University of Florida and co-author of the study, said at the press conference. "It's not something you would want to breathe in. It would damage your lungs. You wouldn't want to put it in your garden to grow your tomatoes," he added.

Though the seedlings grown in lunar soil were stressed and stunted compared with plants grown in Earth soil, they still sprouted and grew. The milestone could supply researchers with lessons on how agriculture could support human outposts in other worlds.

Still, we are a long ways off from space farmers tilling lunar soil and living off the land. The moon's atmosphere lacks the constant access to oxygen and water needed for plants to thrive. Further research on lunar gardening might help would-be space travelers to grow food source during long-term missions.

"We need to work out how to make the plants grow even better in this regolith substrate," Sharmila Bhattacharya, chief scientist for astrobionics at NASA, who was not a part of the study, told CNN. "For example, do we need to add other components to help the plants along, and if so, what are they? Are there other plants that can adapt better to these regolith substrates, and if so, what traits make them more robust to these environments?"

Bhattacharya added: "That's what's so exciting about science; each new finding leads to more unique and transformative results down the road, which we can then use to help improve sustainability for our future space exploration missions!"